As we look toward a holiday steeped in tradition—Thanksgiving—it affords an opportunity to broaden our ideas about how that day is celebrated with food and recipes that have their own stories of gratitude to tell.

Turkey is the oft invited main entrée to Thanksgiving dinner, and it won’t likely be usurped as the mainstay anytime soon. But, for some, the meal celebrates cultural traditions that have woven their ways across oceans, over land and through generations of citizens.

Around Ivy Chang’s Thanksgiving and Christmas tables, guests have come to expect her version of Peking Duck, which she first prepared in 1978 after receiving The Cooking of China cookbook as a Christmas gift a few years earlier. “My parents had eaten [Peking] Duck in China, but very few Chinese restaurants at the time served it [in the Twin Cities],” the Minnetonka resident says. “[Once moving to the U.S.], my father [Robert W.H. Chang] took us to the only Chinese restaurant in St. Paul to eat it.”

Chang took her turn preparing the duck, but, as many cooks do, she altered the recipe. “I changed it somewhat because I didn’t want to set fans on it to blow dry the duck skin. After the duck roasted, I served it to my father and sister at Thanksgiving. We decided the duck needed certain changes to taste like restaurant duck. I made changes a few times after that year to duplicate the taste.” For the last 20 years, Chang has made Peking Duck during the holidays for her family. “Now, it is a tradition,” she says.

“I like to make the duck, even though it requires many days [to prepare] because so many people enjoy eating it,” Chang says. “The Chinese, especially, understand the process and taste.” To truly appreciate the recipe, she encourages those unfamiliar with Peking Duck to order it at a restaurant before trying to make it themselves. “Then they would understand the recipe and can make it,” she says.

Ready to try? To get started, procuring duck from a reputable market is important. Chang relies on Von Hanson’s Meats (which has several Twin Cities locations) and emphasizes the need to purchase a fresh, not frozen, duck. “My family can tell the difference,” she says.

Next? “The most important thing is to dry the skin as much as possible before progressing to the next steps,” Chang says. “The duck I make requires three days from hanging the duck to roasting it. The skin must be dark and crisp when it is put into the wrapper. The duck and skin are served inside a soft flour wrapper with hoisin sauce.”

Finally, Chang recommends ideally-suited side dishes, including wild rice and plenty of vegetables. Seafood can also be a nice accompaniment to the entrée. “The duck can also be served as an appetizer, or other Chinese dishes will be served after the duck,” she says.

One would be remiss in not inquiring about the Thanksgiving dinner finale. What about dessert? “We don’t usually eat dessert,” Chang says, but if guests are game for a sweet ending to the meal, she’ll offer her homemade rum cake.

Who is next in line to take the recipe reins from Chang? It doesn’t appear that anyone is stepping to the fore, which is understandable when it comes to making a labor-intensive dish. “Now with the times, we keep moving forward in recipes and with food,” Chang says. “A lot of people would think it’s easier to go

out and get [Peking Duck at a restaurant].” In the meantime, make no mistake, she enjoys her role as the recipe keeper. “If they like it, I’ll keep making it,” Chang says.

Lessons Learned

“My mom was a wonderful cook, so I learned from her,” Chang says, noting that she also remembers learning about cooking from one of her grandmothers and the staff the family employed while living in Taiwan. “We were outside playing, and the servants would be outside prepping for dinner.” Chang would watch them alongside her cousins. “It was just fascinating,” she says, but admits she didn’t realize what she was learning at the time. “Later, when I was starting to cook, I understood what I had been watching,” Chang says.

Thankful for the Journey

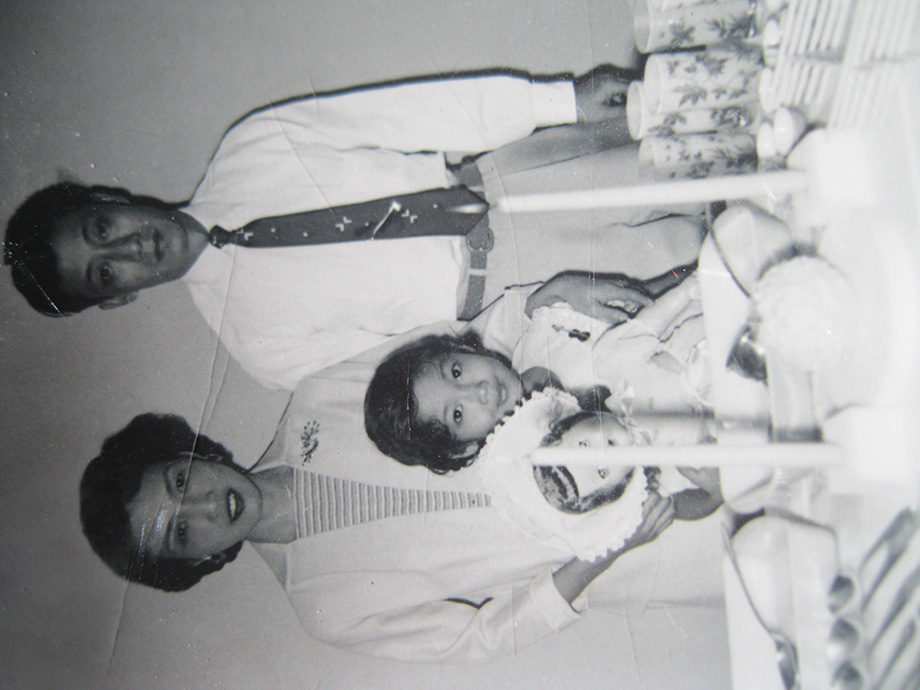

“I was born [in 1947] in Beijing to a political family,” Chang says. “My grandfather served under Chiang Kai-shek in the Nationalist Party. In 1949, when the communists took over China, we had to leave, and [we] went to Taiwan. My father was in Minnesota [beginning in 1948] to study for his master’s and Ph.D. degrees. My mother and I could not enter [the U.S.] because [the country] did not allow family members to come with the person studying.”

During the Korean War (1950–1953), Chang and the rest of her family still could not enter the U.S., and her father went to work at General Mills. According to Chang, the General Mills CEO at the time asked Hubert H. Humphrey, who was serving as a U.S. Senator from Minnesota, to intervene on behalf of others facing a similar situation. Eventually, Chang and her mother, Jean Chang, arrived in Minnesota in September 1955, when she was 8.

New to the country, Chang didn’t speak English, but her parents wanted her to learn American English (Her father learned English by way of British teachers at his boarding school in China.), so she had to learn the language on her own. “It took me one to two years to learn,” Chang says. “I faced a lot of discrimination from the students in my class. I had to really study at hard, even at home.”

The family settled in Roseville, and Chang’s only sibling, a sister, was born in 1958 in St. Paul. Chang attended Roseville schools and graduated from Alexander Ramsey High School in St. Paul. She graduated in 1970 from the University of Minnesota with a degree in journalism and

a minor in anthropology.

“As I was looking for a job, I was lucky the [U of M] journalism school received a call from Burlington Northern that week and wanted a graduate. I interviewed, along with others, and [Burlington Northern] offered me the job.” Chang’s career (3M, International Multifoods, St. Paul Public Schools and Reed Business Inc.) eventually moved her to launch her own public relations firm in 1992, and until 2021, it served mostly small and minority-owned businesses.

Chang’s father retired in 1991, moved to Hong Kong and died in 1999. Her mother passed away in 2008 in New Jersey. With no children of her own, the family continues through Chang’s sister’s two sons and a granddaughter.

In learning about her familial history, it brings to mind the question: What is Chang grateful for this Thanksgiving? “That we have an extended family,” she says. “I’m grateful for the life I’ve had. I’ve had a great life.” She also says that, while she, her immediate family and ancestors have faced discrimination throughout history, “We’ve survived all that. We’ve had some good times, and we’ve advanced in this culture.”

Peking Duck

(Ivy Chang)

- 1 fresh duck, 5-6 pounds

- 3 stalks green onions, cut into 3-inch lengths

- 6 cups water

- 4 large slices of ginger (1/8 inch, peeled)

- 1/4 cup honey

- hoisin sauce

Preheat the oven to 375 F. Wash the duck inside and out. Cut away excess skin. Secure a thick string under the wings, and tie a knot on the top of the duck. Check outdoor temperature, making sure it is 40 to 50 F. Hang the duck outside close to the house, making sure it is away from animals and birds. Put newspapers under the duck. If the outdoor temperature drops in the evening, bring the duck inside, and hang it on a clothesline or on pipes near the ceiling.

During the morning of the second day, check the skin. (It should be drier.) Hang it outside again, but bring the duck inside during late afternoon.

Combine the rest of the ingredients in a large pan, and place on high heat. When the solution comes to a boil, turn off the stove and wait 60 seconds. Take the duck by the string and drop it into the solution. Turn the duck slowly several times for about five minutes. Remove the duck, and hang it outside. Fat should be dripping out of the duck. After an hour, take a knife and slide it under the skin to separate it from the duck meat. Allow the duck to hang until the next day.

The next day, place the duck inside an oven bag, cutting small holes on top of bag. Set the duck on a rack inside a roasting pan, and place in oven. Roast for an hour. Turn oven to 300 F., and turn the duck breast side down. Roast for a half hour. Turn oven back to 375 F., and turn duck breast side up and roast for the final half hour. Remove duck to a cutting board. Wait a few minutes. Cut the skin from the breast, back, sides and legs of the duck, 2- by 3-inch rectangles. If fat is under the skin, scrape off the fat. Arrange the skin on a heated platter, separate from the duck. Cut the wings, and place on another platter. Cut the meat into longer slices, and place them with the wings. Use Mandarin pancakes or tortilla wraps, slightly heated. Brush hoisin sauce on the wraps with scallions; add the duck and a few pieces of skin on top. Fold the end, then the sides to form a cylinder, and pick up with your fingers to eat.

Rum Cake:

(Ivy Chang)

- 3 eggs

- ½ cup plus 1 T. water, divided

- ½ cup vegetable oil

- 1 cup rum, divided

- 1 box yellow cake mix

- ½ cup margarine, plus more to coat the pan

Grease a Bundt pan or angel food cake pan with margarine. Set the oven to 350 F. Beat eggs in a large bowl. Add ½ cup of water, ½ cup oil and ½ cup of rum, and mix again. Add the cake mix to liquid mixture, and beat until the cake mix is dissolved. Pour into your desired pan, shake to even the top of the mix. Place the pan in the oven for 40 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean from the cake. Cool for one hour, and turn upside down on a cookie sheet or plate. Poke holes evenly on the bottom of the cake, turn cake to the top side and poke holes on top.

Rum sauce: On low heat, stir ½ cup margarine, 1 T. water and ½ cup rum; stir frequently at a low boil for five minutes. With a small spoon, pour sauce into each hole. Any remaining sauce can be spread on top or bottom of the cake.