Were you hot or cold? Did you have coveted snacks to share, or did you spend time at the table longingly looking at other kids’ goodies? Did you sport the latest lunch box, or were you a brown bagger? Sit alone or with your crew? Face it; school lunch could serve up a whole lot more than rectangle-shaped pizza slices, late-in-the-week hotdishes made from early-in-the-week entrée leftovers or trade-worthy goodies from home.

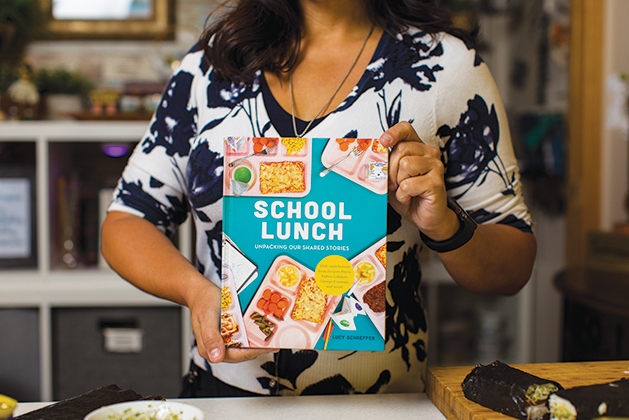

Regardless of what you brought, who you sat with or where you went to school, parts of the school lunch experience are universal, and author Lucy Schaeffer examines the collective experience in School Lunch: Unpacking Our Shared Stories (Running Press, 2020).

The book includes 70 interviews from around the world, including the U.S. and 25 countries. Schaeffer taps into the memories of a variety of people, including Padma Lakshmi (co-host of Top Chef), Jacques Pepin (French-born American chef), George Foreman (former professional boxer), Marcus Samuelsson (chef and TV personality), Gail Simmons (food writer and co-host of Top Chef), Joy Behar (comedienne and co-host of The View), Katie Lee Beigel (chef and co-host of The Kitchen) and Lake Minnetonka area Realtor Natalie Webster.

“[Schaeffer] found me through someone else she was interviewing for the book. They knew I was from Hawaii and have a crazy love of Spam, which also happens to be made here in Minnesota,” says Webster, a Lake Minnetonka Magazine advisory board member. Growing up, she attended a number of schools on the island of Oahu and Aiea High School, which was not far from Pearl Harbor.

“Growing up in Hawaii meant being exposed to multiple cultures, including their culinary choices. Walking through the cafeteria at my school, I would see more dishes like Spam musubi, which I would bring, or Asian-inspired noodle dishes, than sandwiches,” Webster says. “Some friends brought dishes made by their grandmas, who lived with them. Multigenerational living was and is very commonplace in Hawaii.”

In the book, Webster says, “My mom, God rest her soul, was not exactly Mom-of-the-Year on this kind of stuff. She worked full-time, that woman was not about to peel and slice fruit for me.” She explains, “My mom worked full-time plus at our family business. This meant my sister and I were on our own most of the time, including when it came to packing a lunch for school. Spam musubi was an easy choice for us to take to school for lunch. It was easy to throw into a bag, along with whatever fruit was ripe in our yard.”

“When I would go to my friend’s house, her mom would cut fruit and prepare snacks for us. I thought this was so cool at the time,” Webster says. “My sister and I were making our own food and fending for ourselves at a young age. It’s what we had to do. Growing up that way prepared us for the real world. Caring for ourselves more than most kids our age meant we also learned to advocate for ourselves. That’s a life skill I carry today ... If I want to accomplish something, I don’t look to anyone else to make it happen.”

Webster agrees that life in a school cafeteria is about so much more than what’s for lunch. “It was the largest social interaction of the school day,” she says. “It’s where trades were made and gossip was shared. Lunchtime was always our time as kids. As I’ve been reading [Schaeffer’s] book, I’m really seeing that this was a universal experience. The food we consumed may have looked different, but the social bonding that occurred over these lunches is what ties many of us together.”

As Webster read the book, she discovered something else. “What strikes me is the vulnerability shared, especially in families that dealt with food insecurity,” she says.

A Conversation with the author

LKM: What was the impetus for the book?

LS: This book started just as a personal photo project. I had intended to make a promotional mailing card for my commercial photography business with a school lunch theme, but once I started interviewing people and gathering stories, I quickly realized it was such a rich subject matter that I wanted to explore it deeper.

What areas of life experience did you cover?

The book includes stories from people ages 6–93, from 25 different countries and as many diverse backgrounds as I could find. For the international stories, everyone is currently an American but grew up around the world. Diversity is the strength of our nation, and I wanted to showcase that. I lived in Brooklyn at the time of making this book and was able to get a large range of ethnicities and background stories from people there. I took a few trips to California, Minnesota, Texas and Florida to shoot stories as well. I was drawn to Minneapolis as a city to meet subjects because of the large Somali refugee community there, which was a viewpoint I wanted to include. Saciido Shaie was a pleasure to interview and photograph, and I loved her story. I also shot Natalie Webster, Catherine Campion, Eli Grubbs and Melinda Nelson in Minnesota.

Did you learn anything about children’s food insecurities?

George Foreman was one of the most poignant lunch stories for me. He grew up very poor, and his family could only afford one meal a day. Rather than go to school empty handed and face ridicule from classmates, he would carefully blow up an empty paper bag and bring that in to look like he had a lunch like everyone else. During lunch, he’d fold it back up, saying he already ate.

Was there an unexpected response from anyone?

I have to admit I was surprised by Jacques Pepin’s lunch story. I reached out to him wondering what a French-born culinary icon would have had as a kid and was expecting a fancy and delicious answer. The truth, however, was that he grew up in wartime and was sent by his mother to a Jesuit school, where they served hard bread that he had to bang on the table to get the bugs out of before he tried to eat it. He would beg and barter with the farm boys, who had jars of duck fat or homemade jam, to try to improve the dismal fare.

Was there a response that resonated with you?

To some extent, all of the stories resonated with me. I think school lunch is such a universal subject that we can all relate to stories that remind us of our own food to stories that are vastly different from our own experiences. I focused on the elementary school days, as when you are a little kid, you are very much at the mercy of the culture and family that you are born into. No matter what we grow up to be (celebrity, rabbi, circus performer, tattoo artist), we all have that shared experience of school lunch.

What did you discover about the social aspect of a school cafeteria?

The school cafeteria is one of the main social arenas of any elementary school. Who you sit with, what you eat, if you bring from home, buy or receive free lunch—all these things matter to kids ... Chinae Alexander [lifestyle personality] moved a lot as a kid and talks about how dealing with the new lunchroom again and again shaped her ability as an adult to take on new situations and have compassion for people.

SPAM Musubi

contributed by Natalie Webster

- 12 oz. of Spam

- ¼ cup soy sauce or coconut aminos

- nori roasted seaweed

- 6 cups cooked sushi rice

- ¼ cup oyster sauce (optional)

- ¼ cup Japanese rice vinegar

- Spam musubi maker (amazon.com)

Prepare the rice in a rice cooker, and cool. Mix in the rice vinegar. Slice Spam and put in plastic bag, and add oyster sauce and soy sauce or coconut aminos. Seal the bag, and marinate for about 15 minutes. Drain off the marinade, and fry the Spam over medium heat, until slightly crispy. Place seaweed (shiny side down) on a cutting board or clean surface. Place the musubi mold across the middle of the seaweed. Add about an inch or more rice to the mold, add Spam, and press down firmly and evenly. Dip your fingers and the mold into water to prevent sticking. Wrap the seaweed around, and seal it with water on your fingers. Enjoy dipped in soy sauce or coconut aminos.

schoollunchstories.com

lucyschaeffer.com

@lucyschaeffer