The Lowertown neighborhood in Saint Paul has seen quite a bit of change in the past year. With CHS Field up and running, and the business that flows in with the Saints, people are spending more time in the neighborhood, and are realizing that Lowertown is more than baseball. It’s a hub for artists in the city. With artist cooperatives and coffee shops displaying local work, it’s impossible to walk through the area and not see evidence of the artistic community.

Artists of all ages and backgrounds find inspiration in the area, and we found three very different artists to give you a peek into the creativity happening near you.

Samual Weinberg, originally from Minneapolis, only discovered he wanted to paint a few years ago. “I guess I always drew, here and there,” he says, “more just like a hobby.” It wasn’t until he went to college that he discovered he could do more than doodle.

“Once I started painting, I pretty much knew right away I wanted to do this,” he says. So, sophomore year he switched his major to art at University of Wisconsin-Stout and kept painting. Now he lives in Lowertown, works as a bar-back by night, and paints by day.

Much of his work has elements of collage, but there’s a lot of invention with each element, he says. “There is sort of an atmosphere of cut and paste.” But these are not a child’s cut-and-paste art projects.

“I’m making narrative paintings and reading a lot of fiction and trying to figure out, ‘What can painting do for fiction?’ ” Weinberg says. To experiment with that, he has started taking elements of his painting and bringing them into the real world. He painted a hamburger T-shirt on one of his characters, then had the T-shirt made to actually be worn. “It was weird to me having this artifact from the painting in our space,” he says. “The fiction starts to become fuller—or more confusing.”

These experiments are part of his approach to art, and as a young artist, Weinberg uses whatever he can get his hands on for the experiments. He’ll start the canvas by first using house paint, “because I get it for free at hardware stores—so I can paint big, and I want to paint big,” he says. He’ll come back over the house paint with oil paint.

Like many artists, he says sometimes finding the time and energy to create can be a difficult task. “I work at night so I can work during the day,” he says. “Something I didn’t account for is, ‘Oh, I’m tired from working all night.’ ” But Weinberg knows he will have a few days a week for painting, and he knows he could always go back to school and become a professor in art. “There’s a lot of different ways to do it,” he says. “The reason I’ve chosen to do it this way is [that] I don’t want to push away that pure struggle yet.”

Like many creative fields, art is there to help the mind work through things, both for the world and for the individual. “The reason I keep doing it is because there are all these problems,” Weinberg says, “and it’s all part of solving these problems.”

Catherine L. Johnson

The fact that Catherine L. Johnson is able to make art is what some might call a miracle—let alone make art that hangs on the walls of major companies in New York, and in the homes of local celebrities.

Originally from Highland Park, Johnson was born with congenital dysplasia, of both hips, right knee and both feet, and spent her first three years in a Shriner’s hospital. It was the 1950s, and parents were only allowed to visit once a week and not allowed to touch their children. While this rule left many children emotionally bereft, Johnson found a way to survive. She would look down at the small flecks of glittering mica in the sidewalk and tile, and see them as stars. “I transformed these things that were ordinary into something sublime,” she says.

Her doctor, Dr. Mark B. Coventry from Mayo Clinic, saw that light in her, she says. “He would take X-rays of my body and he would not see bone, he would see my spirit. So he would always tell me, ‘Only let those who honor and respect you come near, and always remain an artist.’ ” So she kept her promise to him, and after years of art school, including at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design—and more than 40 reconstructive surgeries—she still has that light.

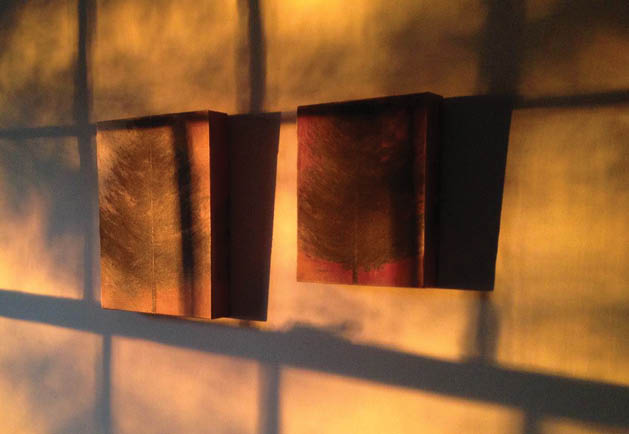

That light might be why her art uses light. Her work changes depending upon where you stand, she explains. “None of my work is static. They all dance. They all move.” The paint she uses has metallic notes and often has the flecks of mica she once saw in the sidewalk. “The whole thing is an experience,” she says of her multi-media art. “It’s a performance, basically.”

Her “Pine Tree: Hope” series is one of those performances. The swooping motion made with the brush turns into a pine tree, but also is a visual of breath, she says. Breathing is something she focused on as a child in the hospital when she wanted to cry but couldn’t because she was wearing a body cast. “So I learned how to tap the rhythm of breathing when I wanted to cry,” she recalls.

These stories behind her art are part of why she values her collectors. Being an artist in the 21st century, in a city that isn’t New York, can be a challenge. Johnson says she’s been lucky, over the years, to find people who understand, allowing her to thrive. “Every single one of them—they are extraordinary people.”

(“Two Pine Tree: Hope 2005” by Catherine L. Johnson; From the private collection of Robert Cohanim)

Amy Cerny Vasterling

“When I was four,” Amy Cerny Vasterling says, “I drew all over the walls, all down the hallway. And my mom knew if she gave me an eraser, I’d just keep drawing with the eraser.” The drawing and art projects continued throughout her childhood but when she got to high school art class, she wouldn’t work on the assigned project—right away. “At the very last minute I would look up at everybody at the table’s [project], and I’d just do it, and I’d be done,” she says. And the teacher would always praise her work. “The people at my table would be so mad.”

Over the years, Vasterling fell in and out of art. She majored in art at Hamline University, but entered the corporate world after graduation; in 2000 she realized she wasn’t happy with it. After starting a family, trying to make art out of her Eagan home, making mass-market greeting cards and magnets and trying to show her work in any available space, she finally rented a Lowertown studio in 2012, and has been there ever since.

Then, of course, she wanted a project to work on. “And it hit me right away,” Vasterling says. Her ability to produce work quickly inspired the “Peace is Abundant” concept. She first planned on making 1,000 paintings, which she quickly realized was not a good plan. “I can’t be everything,” she says. Instead, she works in increments of 50; each set is connected and an experiment within itself, all vary in size, from 10 by 20 feet, to 2 by 2 feet. But Vasterling’s favorite part of the project is that fact that, as she says, “I always think, when you’re buying one of these, you’re part of this bigger concept.”

Art means different things to different people. Vasterling says, “I want to make art that just comes out of me, and trust that it’s for somebody.”

“One of the most important things as an artist is to create in your life, to stay inspired and joyful by what you do,” she says. “And I think a lot of artists become bitter because it’s so tough.” There are overhead costs like canvas and paint. But, she says, “You [the artist] can’t say to yourself, ‘I can’t afford that.’ You have to say, ‘How can I afford that?’”

(“PIA (Peace is Abundant) Jazz Music” by Amy Cerny Vasterling)

See the works of these and other artists at the Saint Paul Art Crawl

October 9, 10 & 11

Friday 6–10 PM Saturday 12–8 PM Sunday 12–5 PM