This article could be one of those trend pieces, about young hipsters from the Digital Age “rediscovering” and reviving analog objects from the 20th century, like vinyl records or handmade chocolates. But Mat Coyle, founder and owner of Excelsior Watch Co., says the market for fine, mechanical watches never really went away.

“There is a misconception that mechanical watches are a lost art, but that isn't true. That market is still growing from 3 to 5 percent every year, depending on what the manufacturers build and sell. And it will always be around, because people like hand-crafted, hand-built things,” says Coyle.

Limited-production mechanical wristwatches are actually a second business for Coyle, who spends his weekdays working with clients as the head of financial planning for a downtown firm. Excelsior Watch Co. began as “a hobby that became a business, after a certain point. It’s built around a love for fine watches.”

He began disassembling and fixing mechanical watches while a student at Drake University in Iowa, in the late 1990s. He repaired and assembled his first working mechanical watch as a gift for his father, who was retiring. “It came out nicely,” he recalls.

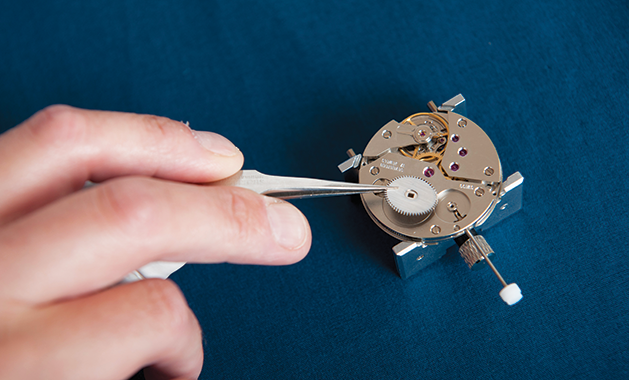

Part of his preparation for launching the company was establishing business relationships with suppliers of the components that go into each watch. Coyle points out that he uses the same base mechanical movements used by luxury watch makers. The movement inside each watch—the mechanism that drives the gears—is crafted by suppliers in Switzerland, which is the world's watchmaking capital. They are “hardy” movements built for a 30-year service life, with servicing every six or seven years. Servicing typically involves disassembling the movement, oiling it, and “making sure it keeps good time,” Coyle explains.

Coyle also uses other upscale materials and components, including rose-gold-plated bridges, brass or steel housings to resist long-term corrosion, and American-made leather straps. Each watch is sold with a custom leather case. “We try to take classic watch designs and [give them] a modern feel,” says Coyle. “Our designs are not frilly; they are very classic and simple.” He does all of the assembly himself, but he can see the day coming when he might have to do some outsourcing, as sales gradually increase. He's currently producing from 100 to 150 watches per year, with models selling for $800 to $2,000 each.

Since launching his company in 2016, Coyle has also employed a non-digital marketing strategy. Although Excelsior Watch Co. has a modern website displaying its products, Coyle doesn't sell watches online. Instead, he sells watches through a handful of select local retailers. His first two outlets are Judd Frost in Wayzata and J. Novachis in Excelsior. One of Coyle’s goals is to build long-term relationships with each customer, which wouldn't be possible using the worldwide web.

Coyle is not aspiring to mass production and mass marketing. “We’re not looking for volume; you’re never going to see our watches in Walmart or Target, or selling on Amazon,” he says. He expects to soon approach another retailer in downtown Minneapolis. “We are associating with retailers who specialize in higher-end products, who provide a high level of customer service,” he says.

In fact, today, there aren't many American makers of fine watches; the most prominent inspiration is Pennsylvania-based Roland G. Murphy.

Eventually, as a long-term goal, Coyle wants Excelsior Watch Co. to evolve into producing the movements in-house. He’s also interested in adding some type of retail space. In a marketplace dominated by cheap, disposable watches, there will always be a demand for handmade, heirloom timepieces. Tick tock.