Not long ago, I was sitting in Sweeney’s Saloon with my literary crew, debating which author had written the best boxing book. About the time our bartender brought our second round, I was about to cast my vote for Norman Mailer’s The Fight until the Poet Mike Finley reminded me of Budd Schulberg’s Sparring with Hemmingway.

But you know how it goes in saloons: Conversations have no boundaries, so before any conclusions were drawn, people we’d never met inserted opinions into our discussion.

Eventually the topic shifted, and one of these new acquaintances asked me if I had been over to the Midway and checked out Element Boxing and Fitness. When I confessed I had never heard of it, I was told it was owned by a young man named Dalton Outlaw, a super middleweight who decided he wanted to use the business degree he earned at Concordia College to form a new culture in the fight game.

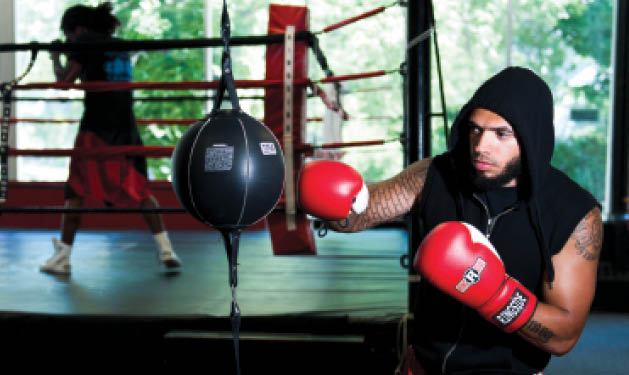

Several days later, I made my way over to Element Boxing and Fitness, LLC. When I walked into the 13,000 square-foot athletic complex, I saw that all the equipment was clean and well organized.

My appointment with Dalton Outlaw was set for 1 p.m. and I was early. I went over to the service counter to ask a staff member to let Mr. Outlaw know I had arrived, but the sales rep was in the middle of signing up a new member.

While I waited, I put my head on a swivel and began examining equipment. Much of it seemed unorthodox. In addition to the heavy bags, speed bags and boxing ring, Element also has a huge free weight section, football sleds and tractor tires like the one RG3 flips in the Gatorade commercials.

As my smirk continued to grow, the sales rep at the counter made his way over and asked how he could help. When I informed him I was there to interview Dalton Outlaw, the young man smiles and answers shyly: “That’s me, sir, thanks for taking time to stop by.”

Both of us grinned for a second after I point out to Outlaw how unfair life is when the boxer’s face is in better shape than the reporter’s.

“I’ve never much liked getting hit,” he responds, chuckling, before telling me our tour had officially begun.

Our first stop was the business center. “This is my mom, Pam,” he says. “Without her and my wife Lacee, this place wouldn’t float.”

Ms. Outlaw extended her hand, shook mine, and before she opened her mouth, I could tell how proud she was of her son.

As we made our way toward the north end of the building, Outlaw mentions matter-of-factly: “My business plan isn’t based on boxing, but building community.”

The enthusiasm in his voice grows as he tells me about the tenants who sublease his building. Outlaw explains that one of his most pleasant surprises was the relationships that have been built between his fighters and one of the tenants, St. Paul Ballet.

“It’s always nice to have a plan when you build community, but sometimes it’s the unexpected things that make it worthwhile,” he says. “I can’t tell you how cool it is when I see my boxers working out with dancers. My fighters work with them on strength training, and in return the dancers show them how to increase their flexibility.”

Another tenant, Push Fitness, offers cycling classes. “Those people are serious, they’re the real deal and I couldn’t be happier that I am connected to them,” he says.

After talking about these key players (which also includes ARJT Athletics), I join Outlaw in his office. Toys were scattered everywhere to the amusement of my host. As I sit down, he says, “I offer no apologies; I love my kids and this space is as much theirs as mine.”

My appreciation of Dalton Outlaw was growing by the second.

Once we were both seated, I ask a question to break the ice.

“Dalton Outlaw, everyone is going to want to know, is that your real name? After that, tell me about your boxing career.”

“Yeah, that’s the name on my birth certificate, but in regard to my career, I fought pro at 168 pounds,” he says, adding that he turned to pro boxing after he opened Element.

“I wanted to prove to myself and the people who believed in me that my boxing skills were on the next level, and show that through hard work and dedication, you can accomplish anything,” he says. “But there came a point when I realized I wanted to build community on the front line instead. When I drew up my business plan, I felt pretty good because boxing as a whole was starting to clean up and repairing its image.”

Outlaw pauses carefully to finish his thought with clarity. “One hurdle I felt I had to get past was Minnesota’s boxing brand, it didn’t have a strong record,” he says. “If you go to Vegas, you’ll meet boxers who have given up everything to pursue their ambition there. The community we are building at Element is giving fighters an alternative training destination.” And Minnesota boxing is increasing in popularity and national recognition with collaborative efforts, he adds.

Next I ask Outlaw if he had a tough time funding his dream.

“At first I thought I was on track, but one thing I learned quickly is there are always additional expenses,” Outlaw says. “Days before I opened, I was short on cash so I sold my car.”

And with that explanation, Dalton Outlaw’s confidence blossoms and he proceeds to do what all good reporters want their subject to do: he hijacks the interview.

“Right now boxing is doing great, but for gyms in general, I hope you’ll let your readers know that over half the people who come to my gym are women who work on cardio and kick boxing,” says Outlaw. “Eighty percent of the people who take boxing lessons are white collar workers. Only a small percentage of people who attend Element Boxing and Fitness dare to step into the ring, and with good reason.”

Outlaw stops once again, took a deep breath and reloaded:

“The club has over 100 members, approximately 20 of them are registered fighters. Team Element is really proud that we have four regional Golden Glove champions and the No. 1 and No. 3 ranked junior boxers are in our program,” he says. “Many of these fighters don’t have the money it takes to fulfill their potential, but we do provide scholarships to struggling families and qualifying youth. In addition to fighting locally, many of my boxers have earned the right to compete in marquee venues.” “How does that happen?” I ask.

“Short term answer is fundraisers, but long term the answer is, and I can’t say it enough, community. If people want to go to a live fight, they have to go to casinos and pay big money,” he says. “How great would it be for Saint Paul if we had a larger athletic complex that caters to more sports and also includes an affordable venue that supports Friday night fights, Saturday dance recitals and Sunday martial arts tournaments? I’m confident this is going to happen. My goal is to make it happen sooner than later.”

Being that Outlaw fought at 168 pounds, I wonder if he idolized heavyweights or boxers in his weight class.

“I’ve never had an idol. I just tried to admire and steal the best attributes of every fighter. If you are going to win in the ring, you can’t employee just one strategy. You beat fighters by boxing and boxers by fighting,” he says.

Now that my new friend was in a good mood, I ask him what strategy he’d use against Rocky Balboa.

“Aw, man,” Outlaw laughs. “I’ve never been a fan of Rocky movies. I know they are meant to be fun, but they send the wrong message. Whenever you tell a kid the best way to become a champion is to learn to take a beating, you’re going to damage them. Successful boxers need to think like chess players and remember it’s all about hitting, then not getting hit. If I were Rocky’s trainer, I would have stopped every one of his fights.“ “I played college football and I feel more comfortable competing in the ring,” Outlaw says. “Society doesn’t understand boxing today. I don’t hear people discussing positive ways for young people to fight anymore. Instead they toss them in jail. Losing a fight in the ring not only teaches humility, it’s also a lot safer than fighting with guns.”

He continues, “There is a higher percentage of concussions in football. All our boxers wear protective headwear and fight in the presence of a referee, doctor and a trainer. Any of these people have the power to stop the fight, and they do. When I played football, I can’t tell you how many times I watched a guy get a concussion and remain on the field. A healthy community would never allow that to happen.”

Ladies and gentlemen, what an honor it is to announce I’ve met the future of boxing in the Capital City, and his name is Dalton Outlaw.

— Danny Klecko

Element Boxing and Fitness offers one free trial visit; enrollment packages start at $49 per month.